This study investigated the prevalence of self-medication practices and associated factors among students at Kenyatta University. A cross-sectional survey design was employed, with a structured questionnaire serving as the primary data collection instrument. Data were gathered as of 26 February 2016 at the university’s main campus through a six-month illness recall. A sample of 385(48.8% male; 50.6% female) established using Fischer’s formula, was drawn from the institution’s 35,000 main campus students and recruited as respondents. Simple random sampling, primary data was collected, coded and analyzed using SPSS version 22. The findings indicated that self-medication is high (73.7%), with 84.2% self-medicating manufactured pharmaceuticals while 8.3%used herbal medicine. Respiratory conditions, like cough, cold, sore throat, accounted for more than half (62%) of the symptoms prompting self-medication. The self-medicated drugs were predominantly obtained from pharmacies (78.7%). Among the pharmaceutical drugs, analgesics was the most popular self-medicated class (50.3%). Pharmacists were the primary source of medication information (29.7%). Paracetamol was the predominant analgesic (58.7%). To address the elevated prevalence, the study recommends strengthened regulatory enforcement, targeted student education on the risks of self-medication, and improved access to affordable healthcare services.

1. Introduction

Globally, self-care practices encompassing proper nutrition, hygiene, and healthy lifestyles are advocated as strategies to alleviate the burden on public health systems (World Health Organization, 2022). However, individual and collective self-care behaviors are profoundly influenced by environmental and socioeconomic determinants (Reshna et al., 2021). In numerous societies, the use of over-the-counter (OTC) medications is regarded as an integral component of self-care, as it mitigates illness risk and enhances overall well-being (May et al., 2023).

For instance, over 80% of adults in the United States reportedly self-medicate with paracetamol or acetaminophen for colds and headaches (Noone & Blanchette, 2018). Similarly, young adults aged 18–25, women, rural dwellers, and low-income populations exhibit the highest self-medication rates (Mendoza et al., 2025).

In Africa, self-medication prevalence varies widely, ranging from 12.1% to 93.9%, with the highest rates observed in West and North Africa (Yeika et al., 2021). Predominant self-medicated agents include antibiotics such as cotrimoxazole, antimalarials, analgesics like paracetamol, herbal remedies, and opioids (Makeri et al., 2025).

In settings characterized by endemic poverty, self-medication emerges as a primary alternative for managing illness due to the unaffordability of formal healthcare services (Noone & Blanchette, 2018). This practice is particularly prevalent in developing countries, where access and affordability of healthcare pose significant public health challenges (May et al., 2023). Individuals therefore frequently resort to a wide array of non-prescribed drugs obtained from local outlets without medical oversight (Sharif, 2017).

The absence of clinical evaluation by qualified providers and the unregulated nature of self-medication heighten vulnerability to multiple risks (Camilleri, 2024). These risks include misdiagnosis, inappropriate drug selection, treatment delays, pathogen resistance, and dosage errors (Rusiz, 2010), alongside adverse drug reactions, allergies, addiction, drug interactions, and masking of serious underlying conditions (Montastruc et al., 2016).

Non-prescribed use of antibiotics and antimalarials has been strongly associated with antimicrobial resistance and parasite resistance across diverse settings (Al-Worafi, 2020). In the United States, opioid-related overdoses linked to self-medication contribute to approximately 130 daily deaths and over one million emergency visits annually (Langabeer et al., 2021), while antibiotic misuse is estimated to account for approximately 35,000 deaths per year (Fong, 2023).

Despite sustained warnings from the World Health Organization regarding these dangers, particularly antibiotic resistance (Rather, 2017), non-prescribed drug use, including OTC medicines, remains widespread. Notably, a substantial proportion of individuals engaging in self-medication are aware of the associated risks but proceed regardless (Camilleri, 2024).

In Kenya, despite the existence of national policy guidelines regulating self-medication, prevalence remains elevated (Kimathi et al., 2022). Commonly self-medicated substances include antibiotics such as amoxicillin, analgesics like paracetamol, antimalarials, cannabis, and traditional herbal remedies (Owuor, 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated self-medication practices across Africa (Kimathi et al., 2022).

Studies among university populations in Kenya have documented widespread self-medication, particularly for respiratory conditions, alongside heightened risks of analgesic overdose (Walekhwa et al., 2022). The present study builds on this evidence by examining the prevalence and determinants of self-medication practices among Kenyatta University students.

2. Methods

2.1 Research Design

The study employed a cross-sectional survey design. Ideally, this approach allows the researcher to collect data at a single point in time. For this research, the cross-sectional research design enhanced collection of data that allowed the study to get a snapshot of prevalence of self-medication practices among university students in Kenya.

2.2 Study Location and Population

The study was conducted in Kenyatta University Main Campus. The institution is located in Kahawa West location, Githurai Division, Kasarani, Nairobi along the Nairobi–Thika Highway. It is about 17–18 km northeast of Nairobi Central Business District (CBD). Geographically, Kenyatta University Main Campus sits on a 1,000-acre piece of land and accommodates about 35,000 students.

The university comprises several schools including environmental science, education, business, economics, law, health sciences, and pure and applied sciences.

2.3 Sample and Sampling Technique

The study population comprised students enrolled at Kenyatta University Main Campus. At the time of the study, the campus had approximately 35,000 students studying in various schools. The sample size was established using the Fischer sample size calculation approach.

The formula used to calculate the sample size was:

\( n = \frac{(p \cdot q \cdot Z)^2}{d^2} \)

Where:

- n is the sample size

- Z is the z-score for the required confidence interval

- p is the expected population proportion having the attribute under study

- q is equal to (1 − p)

- d is the margin of error

The study used a 95% confidence interval, corresponding to a z value of 1.96. Since p was assumed to be 0.5, q = 1 − p = 0.5. Substituting these values into Fischer’s formula yielded a sample size of 385.

A sample of 385 students was randomly selected and recruited as study participants.

2.4 Data Collection Instrument

A pretested, semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect relevant information. The inclusion of both open-ended and closed-ended questions allowed for comprehensive data collection on the subject. The questionnaire was prepared in English.

2.5 Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected through administration of questionnaires to respondents selected randomly. This task was carried out by trained enumerators. Verbal consent was sought from respondents prior to participation. Questionnaires were completed in the presence of enumerators to assist participants who experienced difficulties during the process.

2.6 Data Analysis

Collected data were coded and entered into Microsoft Excel and subsequently analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 22. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were computed at a 95% confidence interval.

2.7 Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Chairperson of the Therapeutic Department in the School of Medicine. The study emphasized respondent confidentiality, anonymity, and informed consent. Participants were assured that all information provided would be treated with confidentiality and used solely for research purposes.

Personal identifiers were excluded from the questionnaires to ensure anonymity. Verbal permission was also sought from respondents before completion of the questionnaires.

3. Findings

Table 3.1

Respondent Demographics

| Factor | Classification | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 188 | 48.8% |

| Female | 195 | 50.6% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 373 | 96.9% |

| 26–30 | 10 | 0.3% | |

| 31–35 | 2 | 0.18% | |

| School | Medical | 53 | 13.8% |

| Non-medical | 332 | 86.2% |

From the findings, 284 out of 385 respondents reported having self-medicated in the past six months, indicating a prevalence of 73.77%. Students enrolled in medical courses demonstrated a higher likelihood of self-medication compared to those in non-medical courses. Frequent illness and lack of medical insurance coverage were associated with increased self-medication practices.

Table 3.2

Self-Medication Practices Reported

| Practice | Observation | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-medication frequency (last 6 months) | None | 101 | 26.23% |

| Once | 48 | 12.47% | |

| Twice | 39 | 10.14% | |

| Thrice | 27 | 7.01% | |

| More than thrice | 172 | 44.6% | |

| Drug origin | Herbal medicine | 24 | 8.3% |

| Pharmaceutical/industrial medicine | 239 | 84.2% | |

| Therapeutic classification | Analgesics | 143 | 50.3% |

| Antibiotics | 35 | 12.3% | |

| Antihistamines | 32 | 11.4% | |

| Cough medications | 31 | 11.0% | |

| Antacids | 19 | 6.5% | |

| Antimalarials | 14 | 4.9% | |

| Source of drugs | Pharmacy | 224 | 78.7% |

Herbal remedies were used by 8.3% of respondents, with commonly cited preparations including neem (Azadirachta indica), aloe vera, honey, ginger, garlic, lemon, and Moringa oleifera. Manufactured pharmaceuticals were used by 84.2% of respondents.

Respiratory conditions accounted for the majority (62%) of symptoms prompting self-medication, followed by pain-related conditions (29%) and gastrointestinal disorders (17%). Malaria accounted for 9%, while urinary tract infections, skin conditions, sleep disorders, and weight loss constituted the remaining cases.

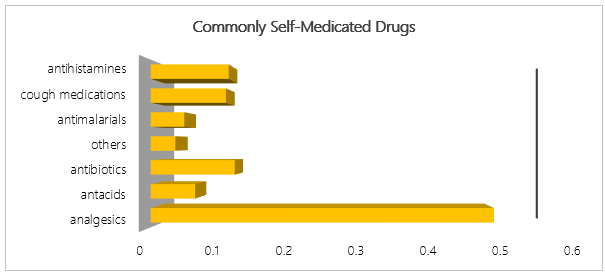

Analgesics were the most commonly self-medicated drugs (50.3%), followed by antibiotics (12.3%), antihistamines (11.4%), cough medications (11.0%), antacids (6.5%), and antimalarials (4.9%). Pharmacies were the main source of drugs (78.7%), and pharmacists were the leading source of medication information.

4. Discussion

The self-medication prevalence and practices among Kenyatta University Main Campus students observed in this study underscore a pervasive engagement in autonomous therapeutic decision-making. The findings corroborate those of Walekhwa et al., who indicated that self-medication is common among university students (Walekhwa et al., 2022). The study further revealed that medical students engage in self-medication practices more frequently than their non-medical counterparts. This disparity aligns with health literacy and professional socialization theory, wherein medical training fosters familiarity with pharmacodynamics, symptomatology, and drug nomenclature, thereby reducing perceived barriers to self-diagnosis and treatment. Salisu et al. aver that such enculturation inadvertently normalizes self-medication as an extension of clinical reasoning, even outside supervised clinical contexts (Salisu et al., 2019).

Frequent illness and absence of medical insurance emerged as significant predictors of self-medication, resonating with Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. Graham et al. indicate that need factors, particularly recurrent morbidity, and enabling factors such as financial inaccessibility converge to propel students toward self-medication as a pragmatic adaptive response (Graham et al., 2017). Bryan further situates this behavior within a rational choice framework, emphasizing how individuals weigh time, cost, and convenience against formal healthcare, often prioritizing immediacy over evidence-based protocols (Bryan, 2018).

The symptom profile driving self-medication, dominated by respiratory and pain-related complaints, mirrors global patterns documented in the self-medication literature and aligns with lay epistemologies of illness (Fitzpatrick, 2022). Minor and self-limiting conditions are frequently construed as manageable through experiential or culturally embedded knowledge, diminishing the perceived necessity for professional healthcare consultation. Conversely, Van der Linden and Schermer argue that the inclusion of malaria and gastrointestinal disorders reflects contextual disease burden, where endemicity and familiarity breed confidence in over-the-counter or previously prescribed regimens (Van der Linden & Schermer, 2022).

The predominance of manufactured pharmaceuticals over herbal remedies suggests the persistence of biomedical hegemony in therapeutic preference, even within self-care paradigms. Analgesics, particularly paracetamol, dominate due to their ubiquitous availability, perceived safety, and cultural framing as first-line palliatives. However, the notable use of antibiotics raises concerns within antimicrobial stewardship discourse (Brown, 2023). Self-initiated antibiotic therapy, often informed by pharmacists or social networks rather than microbiological evidence, exemplifies diagnostic substitution and contributes to selective pressure for resistance. This reflects a public health externality of individual agency, as articulated by Cowen and Schliesser (Cowen & Schliesser, 2024).

Drug acquisition patterns further reinforce the pharmacy-centric model of self-medication in resource-constrained settings. Community pharmacies increasingly function as quasi-clinical spaces, dispensing not only medications but also diagnostic legitimacy (Cowen & Schliesser, 2024). Household stockpiles and informal exchanges embed self-medication within domestic health economies, blurring boundaries between prescribed and autonomous use.

Information sources underpinning self-medication practices further reflect social cognitive theory dynamics. Pharmacists serve as accessible health intermediaries and de facto gatekeepers in the absence of physicians, blending professional authority with commercial imperatives. Peer and familial networks perpetuate therapeutic mimicry, where prior outcomes reinforce future choices irrespective of clinical validity. The marginal role of digital or formal training sources underscores a disconnect between information availability and critical appraisal capacity among students.

5. Conclusion

This study reveals self-medication as a dominant health-seeking strategy among Kenyatta University Main Campus students, driven by medical training, frequent minor illnesses, and limited access to medical insurance. The preference for manufactured drugs particularly analgesics and antibiotics sourced primarily from pharmacies and guided by pharmacists or social networks reflects a blend of biomedical trust and pragmatic autonomy.

While such practices may enhance individual empowerment and autonomy in health decision-making, they simultaneously pose risks including misdiagnosis, adverse drug reactions, and the acceleration of antimicrobial resistance. These findings underscore the inherent tension between individual agency and broader public health imperatives. Theoretically, the results align with health literacy frameworks, professional socialization theory, and Andersen’s behavioral model, illustrating how knowledge, perceived need, and structural barriers interact to shape medicine access and utilization behaviors.

In resource-constrained settings, pharmacies play a pivotal role in healthcare access; however, they may also function as unregulated nodes within the self-care ecosystem. To mitigate associated risks, integrating accessible formal healthcare services with guided patient autonomy offers a viable path forward. Such an approach can ensure that student empowerment does not compromise individual safety or societal well-being.

Policy and practice interventions should emphasize strengthened regulation of drug advertising and pharmacy practices, expansion of insurance coverage to improve healthcare access among vulnerable populations, and the integration of responsible self-medication education within academic curricula. Collectively, these measures can support safer self-care practices while preserving the benefits of informed autonomy.

References

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being, 2022 revision. World Health Organization.

- Reshma, P., Rajkumar, E., John, R., & George, A. J. (2021). Factors influencing self-care behavior of socio-economically disadvantaged diabetic patients: A systematic review. Health Psychology Open, 8(2), 20551029211041427.

- May, U., Bauer, C., Schneider-Ziebe, A., & Giulini-Limbach, C. (2023). Self-care with non-prescription medicines to improve health care access and quality of life in low-and middle-income countries. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1220984.

- Noone, J., & Blanchette, C. M. (2018). The value of self-medication: Summary of existing evidence. Journal of Medical Economics, 21(2), 201–211.

- Mendoza, A. M. B., Maliñana, S. A. A., Maravillas, S. I. D., Moniva, K. C., & Jazul, J. P. (2025). Relationship of self-medication and antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Public Health and Emergency, 9.

- Yeika, E. V., Ingelbeen, B., Kemah, B. L., Wirsiy, F. S., Fomengia, J. N., & Van der Sande, M. A. (2021). Comparative assessment of self-medication with antibiotics in Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 26(8), 862–881.

- Makeri, D., Dilli, P. P., Pius, T., Tijani, N. A., Opeyemi, A. A., Lawan, K. A., et al. (2025). The nature of self-medication in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 197.

- Sharif, M. D. (2017). A survey on practice and prevalence of self-medication with antibiotics by parents of children. Doctoral dissertation, East West University.

- Camilleri, M. (2024). Educating the general public on the risks of self-medication. Master’s thesis, University of Malta.

- Ruiz, M. E. (2010). Risks of self-medication practices. Current Drug Safety, 5(4), 315–323.

- Montastruc, J. L., Bondon-Guitton, E., Abadie, D., Lacroix, I., Berreni, A., Pugnet, G., et al. (2016). Pharmacovigilance, risks and adverse effects of self-medication. Therapies, 71(2), 257–262.

- Al-Worafi, Y. M. (2020). Self-medication. In Drug safety in developing countries (pp. 73–86). Academic Press.

- Langabeer, J. R., Stotts, A. L., Bobrow, B. J., Wang, H. E., Chambers, K. A., Yatsco, A. J., et al. (2021). Prevalence and charges of opioid-related visits to US emergency departments. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108568.

- Fong, I. W. (2023). Antimicrobial resistance: A crisis in the making. In New antimicrobials: For the present and the future (pp. 1–21).

- Rather, I. A., Kim, B. C., Bajpai, V. K., & Park, Y. H. (2017). Self-medication and antibiotic resistance. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 24(4), 808–812.

- Kimathi, G., Kiarie, J., Njarambah, L., Onditi, J., & Ojakaa, D. (2022). Antimicrobial use among self-medicating COVID-19 cases in Kenya. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 11(1), 111.

- Owuor, I. A. (2022). Effect of community mobilization intervention on self-medication with antimicrobials. Doctoral dissertation, Maseno University.

- Walekhwa, M. N., Elizabeth, S. N., Otieno, F. O., & Wambugu, E. N. (2022). Prevalence of self-medication practice among Kabarak University students. Journal of Science, Innovation and Creativity, 1(1), 37–42.

- Graham, A., Hasking, P., Brooker, J., Clarke, D., & Meadows, G. (2017). Mental health service use and Andersen’s Behavioral Model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 170–176.

- Bryan, L. (2018). A Limited Rational Choice Theory in Local Public Health Decision Making.

- Brown, N. (2023). Antimicrobial resistance: Discourse, practice and relating. In Handbook on the Sociology of Health and Medicine (pp. 291–307). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Van der Linden, R., & Schermer, M. (2022). Health and disease as practical concepts. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 25(1), 131–140.

- Fitzpatrick, R. (2022). Lay concepts of illness. In The Experience of Illness (pp. 11–31). Routledge.

- Chow, S. C., Shao, J., Wang, H., & Lokhnygina, Y. (2017). Sample size calculations in clinical research. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Salisu, W. J., Dehghan Nayeri, N., Yakubu, I., & Ebrahimpour, F. (2019). Challenges and facilitators of professional socialization. Nursing Open, 6(4), 1289–1298.

- Cowen, N., & Schliesser, E. (2024). Novel externalities. Public Choice, 201(3), 557–578.